A Very Short History of the Transition from Silent to Sound Movies

by Emily Thompson

© Emily Thompson 2011

In 1877, Thomas Edison invented the phonograph and for the first time ever, people could record sound, save it, then listen to it later at another time and place. To make a recording, a person spoke or sang into a big horn. This horn collected the sound energy and sent it to a needle, which wiggled up and down as if it were being tickled by the sound. As the needle wiggled, it cut a long wavy groove into a record made of soft wax, which was spun in a circle underneath the needle. After the recording was made, you could play the record back by placing the needle back at the start of the groove and spinning the record in circles again. This time, the needle rode the wavy groove like a roller coaster. As it moved up and down, it recreated the sounds that had been recorded earlier, and it sent them out of the horn for people to hear again. It seemed almost magical to hear a person's voice coming, not from their own mouth, but from the horn of a machine that remembered exactly what they said and that sounded just like they did.

In the 1890s, Edison invented moving pictures, or movies. A long strip of tiny photographs was captured on film by a special camera, so that each picture was just a little bit different from the ones before and after it. The strip of film was later run through another machine, a projector, that would blend the different pictures together to create the illusion of motion and project the movie onto a large screen in a theater. Edison thought that, if he could unite the sound of his phonograph with his moving pictures, he could create the illusion of life itself—a picture of a person that could move and speak, as if it were alive.

Unfortunately, these two inventions didn't want to work with each other in the way that Edison desired. It was very difficult to synchronize, or "sync," the different machines—to make them work precisely together—so that the recorded sounds of a person's voice would match the movements of their lips seen in the moving pictures. Also, the sound recordings were not very loud, so it was difficult for more than just a few people at a time to hear them.

Still, each invention became successful on its own. People were now able to go the store and buy records of music to bring home and play on their phonographs. They no longer had to sing or play a musical instrument themselves, but could instead just choose a record and let the machine make the music for them. They also began to go out to new movie theaters, where dramatic stories told through the silent moving pictures became very popular. Since there was no recorded sound to accompany the movies, the words that the characters spoke would appear on screen, in special pictures called "titles" that moviegoers read like in a book. Most of the time, though, the actors conveyed their thoughts and moods through their facial expressions and their actions, without speaking a word.

One of the most famous movie actors was a man named Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin always played a character called The Little Tramp, a poor but elegant man who often got into trouble even though he had a good heart. The Little Tramp never spoke, but audiences could tell what he was thinking and feeling just by looking at his face and the ways that he moved his body, and people all over the world loved his films.

Since moving pictures like Charlie Chaplin's were silent, theaters hired musicians to play music during the films so that people would have something to hear. The musicians sat in a pit below the screen and played music that fit the mood of what was happening in the movie: sad music when the baby was sick, scary music when the monster approached, and happy music when the lovers got married. For those who could hear it, the music made the movie more enjoyable. But people who couldn't hear, like the character of Rose in Wonderstruck, were still able to follow the story on screen by watching the actors and by reading the titles. By the 1920s, many people—hearing and deaf—went out to the movies several times a week to enjoy the show.

At this time, another group of inventors tried to accomplish what Thomas Edison had not been able to do—to bring together movies and recorded sound. They now had a new tool: they could use electricity to make and play their sounds, just like the telephone and radio did. In fact, these inventors worked for the telephone company. They used small microphones instead of big horns to collect the sounds, and they had devices called amplifiers that could make those sounds louder. With electricity, they could make recordings that were loud enough for everyone in a large movie theater to hear. Electricity also made it easier to keep the sound in sync with the image. They took their invention to Hollywood—where most movies were made—but none of the movie men there wanted to use it. "Who needs sound?" they argued. "Everyone loves silent movies."

One studio, however, felt differently. The Warner brothers—Harry, Al, Sam, and Jack—had opened their first movie theater in Pennsylvania in 1903, showing movies that other people had made. It was a success and over the years they built many more theaters across the United States. The brothers also began to make movies themselves, to show in these theaters, but most of the movies they made weren't very successful. In 1925, they were looking for a way to make their movies more popular, and Sam suggested that they give sound a try.

Sam Warner liked to listen to the radio as much as he liked making movies. He had studied how radio worked, and had even built a radio station to advertise the Warner Bros. movies. So when the telephone inventors came to Hollywood and showed him their new sound movie system, he was very interested in what he saw and heard. Sam knew that you could use the phonograph to record voices and that you could make movies where the actors talked to each other. But he and his brothers, like everyone else in Hollywood, thought that no one would want to hear actors talk. They decided to keep making silent movies, but to use the new invention to record music to accompany the silent pictures. The record would replace the live musicians in the theater. Many small town theaters could only afford to hire a single piano-player to accompany their movies, but with these new sound movies, a recording of a full orchestra could be played, and the Warner brothers though that people would like this better. It also meant that the brothers got to choose for themselves what kind of music was heard alongside their movies, rather than each individual theater musician deciding what to play. Everyone who went to a Warner Bros. movie—no matter where they lived, big city or small town—would now hear the same music, just as they all saw the same moving pictures on the screen.

The new sound movies were called Vitaphone movies, which means "the sound of life." The first Vitaphone movie, called Don Juan, was a romantic adventure about a famous swordfighter and the many women he loved. A recording of an orchestra accompanied the action on screen, and the record also included some sound effects, like clashing swords and ringing bells, that were synchronized perfectly with the action on screen. Don Juan was a big success and Thomas Edison's dream of combining the phonograph and the movies finally came true. The Warner brothers celebrated their success and planned to make additional Vitaphone movies. Meanwhile, the other movie-makers in Hollywood shook their heads and said, "It's just a fad."

But it wasn't just a fad, and as the Warner brothers made more and more Vitaphone movies, sound movies became even more popular. There were silent adventure stories with recorded orchestral music like Don Juan, and there were also short films where famous singers and comedians sang songs and told jokes. Moviegoers lined up to see them all. In 1927 the Warner brothers made a movie starring a famous singer named Al Jolson. In this movie, The Jazz Singer, Al Jolson's character sang songs and in one scene he also talked and kidded with the woman who played his mother. Audiences really liked this scene, and the Warner brothers realized that people did indeed want to hear the actors talk.

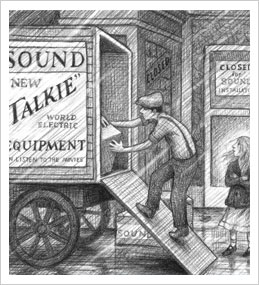

The rest of Hollywood, too, finally realized that this was not just a fad, and they all now rushed into making sound movies themselves. But it was hard to catch up. In order to make sound movies, you had to buy a lot of expensive new equipment for recording sound, and you had to find and hire people who knew how to use it. If your studio was in a noisy location, near traffic or with airplanes flying overhead, you had to construct a special new building that would keep out all that noise. Some actors had funny-sounding voices or heavy accents that made them hard to understand. Their voices would not work for sound movies, so new actors with good voices had to be found and turned into movie stars. Actors now had to memorize their lines ahead of time and stand still when they spoke, to ensure that the microphones would catch the sounds of their voices. And directors could no longer shout out instructions to the actors while the cameras were rolling. The microphones were very sensitive and could even pick up the whirring noise of the cameras. To keep that noise off the recording, the cameras—and cameramen—were put inside special boxes that muffled the sounds. Cameramen sweated inside these boxes like turkeys being roasted in an oven, and they also complained that they weren't able to move their cameras around any more since that, too, made unwanted noises. Everyone who worked to make movies had to learn a whole new way to do their job when sound movies were made.

Workers in the theaters also had to re-learn their jobs. Projectionists worked in a tiny booth way up high at the back of theater, running the films through the projection machines that brought the films to life on screen. These men now had to operate phonographs as well as projectors, so their job became twice as difficult. Sometimes when a record was played, the needle would skip, or jump around, in the groove and the synchronization between the sound and the picture would be lost. If the sound no longer matched the picture, audiences would angrily boo and stamp their feet until the projectionist fixed the problem. But if the projectionist's job became much harder, at least he still had a job. Theater musicians were not so lucky. When a theater installed a sound movie system, it no longer needed the live musicians to perform from the pit each night, so all those men and women lost their jobs. A few lucky musicians in Hollywood, who performed in the studios where the recordings were made, were now heard by moviegoers across the nation. All the other musicians had to find a new way to make a living.

Audiences too, had to change and adapt to sound movies. They had to sit quietly, in order to be able to hear the voices of the actors on screen. And people who were deaf or hard of hearing now struggled to understand the stories. Some theaters had special headphone sets, to make the recording louder for people who couldn't hear well. Thomas Edison himself was very hard of hearing, so he might have used one of these devices. But most theaters didn't have them, and if a person were fully deaf these headphones were of no help anyway. A deaf person might have been able to read the lips of the characters on screen if the actors had faced the camera while they spoke. But if the actor had turned away from the camera, there were no clues about what was being said, as there were no longer any titles to read. There wasn't as much body language to read either, since the actors had to stand still when they spoke. Sound movies had much less movement and action than silent movies, and since they were mainly filled with scenes of actors talking, people began to call the new movies "talkies." It was much harder for people who couldn't hear well to enjoy the talkies.

Within a few years, however, things got better and by 1930 sound movies were as action-packed as the silent films had been. New, quiet cameras meant that cameramen could come out of those hot boxes and move their cameras around again, and microphones were modified to make it easier for the actors to move around while they talked. A new kind of film was invented where the sound recording was printed right onto the film itself, instead of being on a separate phonograph record. The sound was recorded as a squiggly pattern of light and dark, and it ran right alongside the pictures on the film. Audiences couldn't see the "soundtrack" on screen, but it now was easier for projectionists to keep the sound and picture in sync.

Even when sound movies got much better, however, one famous actor still chose never to speak in his movies. Charlie Chaplin's Little Tramp remained silent, expressing his feelings not through his voice, but through his eyes, face, body, and movement. For this reason, his stories continued to speak to the whole world, including people who were unable to hear, as he spoke in a language that everyone could understand.

EMILY THOMPSON is Professor of History at Princeton University. She studies the history of technology, and teaches a course at Princeton on the history of the phonograph. She is working on a website about noise in New York City in the 1920s (link to come) and is also writing a book about the transition from silent to sound movies in the American film industry. In 2005, she was named a MacArthur Foundation Fellow.